Learning to Listen

I have a fabulous, eclectic group of student riders. The youngest started at 4, the oldest….well, let’s say sixty something. A handful of youngers start riding here, and each first lesson with a new child begins with Spanky, our Welsh/Quarter Horse gelding. Up they go, some bravely and happily; others, not wanting to let go of their mothers. The latter are questionable students--are they here because they are hesitant horse enthusiasts, or because a well intended parent wishes for them to begin lessons? It is a question I must find a way to resolve, before deciding whether to continue. We begin with a walk down the length of the arena, stop, turn, walk back. In the case of the hesitant horse enthusiast, soon, the death grip on the horn loosens, and their shoulders begin to drop. At some point, a smile may even appear, or a giggle. I’ll ask them if they are enjoying the ride, and if they are, to reach down and pet Spanky and tell him what a good boy he is. This is a actually trickery. It’s not only about getting the rider to appreciate the service of the horse. My ulterior motive is to let the rider see she can, in fact, release her death grip on the horn, and trust the horse will keep her aboard while she pets him.

And so the lessons progress. Just about the time a student is feeling good about something, confident in something, I’ll toss in something to challenge them, mentally, emotionally, or physically. I watch very carefully, looking for stress and tension in the riders’ muscles, facial expression, or breathing, and decide whether they’re ready for “the next thing”, or not. Sometimes, I’m mistaken. But somewhere on the scale, between the look of eager willingness, the look of hesitation and insecurity, and the look of terror, I will decide whether to advance, stay the course, or retreat.

And so the lessons progress. Just about the time a student is feeling good about something, confident in something, I’ll toss in something to challenge them, mentally, emotionally, or physically. I watch very carefully, looking for stress and tension in the riders’ muscles, facial expression, or breathing, and decide whether they’re ready for “the next thing”, or not. Sometimes, I’m mistaken. But somewhere on the scale, between the look of eager willingness, the look of hesitation and insecurity, and the look of terror, I will decide whether to advance, stay the course, or retreat.

"The tactical part of the equestrian art, the part we will exclusively study now, is not easy to describe in a text. The mobile life that constitutes the essence of the art may easily become lost in letters and prints. Besides we have an additional problem that is difficult to overcome. Every situation is unique in this art but I have made lots of efforts to make the description clear, so that an inexperienced rider may find the information useful. Equestrian art constitutes innumerable observations. Small details may have great effects, but will usually pass by unnoticed by the young rider’s attention. For these reasons, general opinions are not applicable, although this is the usual way to present the subject.” Adam Ehrengranat, 1836

Horses are no different. They worry, they are afraid, insecure, and apprehensive. Some are more trusting than others, some less. Either way, the real lesson cannot begin, until the fears and tensions have dissolved. A horse will present fear and tension in infinite forms of resistance, and so general opinions are not adequate. The real information cannot be found in books or theory, but in the horse. In his soft eye, in his open ear, in his nostril flare and the frown of his mouth. In his cocked head, arched neck, or swishing tail. The most valuable information the educated equestrian can get comes from the horse, IF she knows how to be attentive to the small details which reveal the state of his mind and emotions.

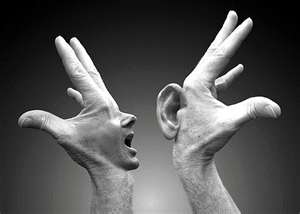

I don’t think of riders in terms of “good” riders or “bad” riders. I see riders and handlers with varying degrees of attentiveness. Are they paying attention to the details of the horse’s expression? Do they understand if the horse is bored, or stressed, or worried? Do they know where his attention is? Are they paying attention to the tempo, the rhythm, the gait when mounted? Do they understand how to find the horses’ feet, and do they know when to ask for a change in posture? The more attentive a rider is to a horse, the more information she can receive, manage, and direct. Attentiveness enables control, and control, grace. As a hearing impaired person has trouble dancing gracefully to music, the “deaf” rider, who doesn’t know how to read and feel his horse, is at a disadvantage, both of grace, and of basic safety.

But learning to listen to the horse is only half the equation. Next week--the other half.

Horses are no different. They worry, they are afraid, insecure, and apprehensive. Some are more trusting than others, some less. Either way, the real lesson cannot begin, until the fears and tensions have dissolved. A horse will present fear and tension in infinite forms of resistance, and so general opinions are not adequate. The real information cannot be found in books or theory, but in the horse. In his soft eye, in his open ear, in his nostril flare and the frown of his mouth. In his cocked head, arched neck, or swishing tail. The most valuable information the educated equestrian can get comes from the horse, IF she knows how to be attentive to the small details which reveal the state of his mind and emotions.

I don’t think of riders in terms of “good” riders or “bad” riders. I see riders and handlers with varying degrees of attentiveness. Are they paying attention to the details of the horse’s expression? Do they understand if the horse is bored, or stressed, or worried? Do they know where his attention is? Are they paying attention to the tempo, the rhythm, the gait when mounted? Do they understand how to find the horses’ feet, and do they know when to ask for a change in posture? The more attentive a rider is to a horse, the more information she can receive, manage, and direct. Attentiveness enables control, and control, grace. As a hearing impaired person has trouble dancing gracefully to music, the “deaf” rider, who doesn’t know how to read and feel his horse, is at a disadvantage, both of grace, and of basic safety.

But learning to listen to the horse is only half the equation. Next week--the other half.

The lesson for the adult or mature rider is not much different, but for the fact they are more discrete with their emotions. At some point in their lives, they learned to put away their fear and tension. Not that the fear and tension went away. It’s just buried, and I have to watch much, much closer to see how the rider is feeling. At some point, the rider needs to set aside all fear, and let their mind go calm and quiet, so that the listening may begin. I watch for that release of fear, of tension, because that’s when the lessons can start in earnest.

5.11.12 TME

Return to Educated Equestrian

Return to Educated Equestrian